2022-12-13

By Stay Out Stay Alive

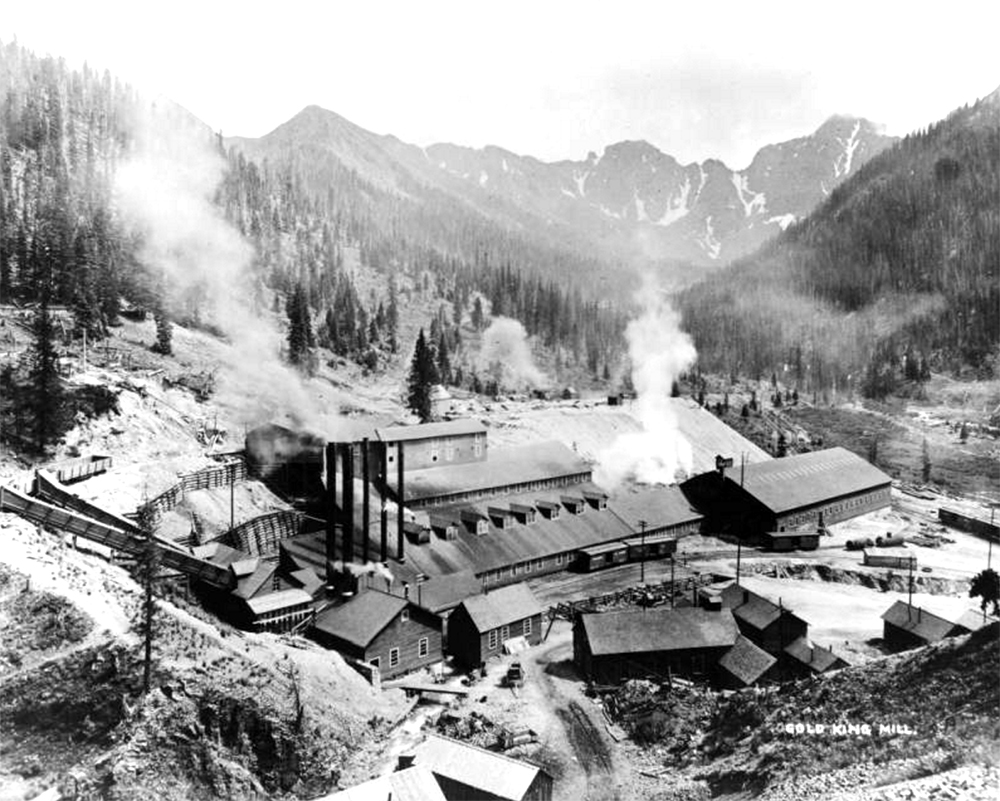

The Gold King Mine in Gunnison County, Colorado, is an excellent example of a historic mine that the Bureau of Land management ruined without fully understanding the mine’s history or potential for the future. Production at the Gold King Mine started in 1886. One report from 1902 says:

“The largest producer in the county, both in ‘tonnage and values, is the Gold King, its ore mined and milled during the year reaching 72,455 tons. The mill of the company consists of an amalgamation and concentration plant, with a capacity of about 200 tons a day. The 80-stamps are of the rapid-drop pattern, weighing 850 pounds each, and the screens are especially made of copper wire for these batteries and have shown a remarkable life. The gold retorts sent from the mill have reached a total value of $400,000, and the concentrates shipped amounted to 14,428 tons, with a valuation of over $700,000.”

View of the Gold King Mill, in San Juan County Colorado; shows gold mine processing facilities, ore cars, cribbing, smokestacks, tailings, and mountain peaks. Taken between 1880 and 1920. Courtesy of the Denver Public – Western History Collection.

Other reports about the Gold King operation confirm how lucrative production was. By the time the Gold King ceased production in the late 1920s, the mine had produced more than 700,000 tons of gold, silver, lead, and copper ore, valued at $8.4 million. Reports also indicate that the grade of ore in the Gold King increased with depth, which might lead one to guess that there is still gold in the mine.

Following the closure of the Gold King Mine, the Sunnyside group of mines also shut down. This changed life in the nearby town of Silverton, Colorado. Once mining money stopped rolling in, the town’s economy began to rely on the tourism industry.

In 1960, operations at the Sunnyside Mine are revitalized. Miners began building an 11,000-foot-long tunnel connecting the American Tunnel to the Sunnyside Mine. The tunnel ran 860 feet under the Gold King Mine. Since the tunnel “deep drained” groundwater, the Gold King Mine became dry. In addition to water drainage, the tunnel provided gravity-assisted ore haulage for the Sunnyside group and helped revitalize mining around Silverton.

Years later, in 1972, on a Sunday morning, when no miners are working, the floor of Lake Emma collapses into the Sunnyside Mine, sending tens of millions of gallons of water gushing through the American Tunnel at Gladstone. This shut down the mine for months. To this day, some former employees are suspicious of the collapse, theorizing that it was planned by a struggling company looking for an insurance payout. For months before the collapse, engineers at the Sunnyside had warned management that they were cutting too close to the lake’s floor. If this mishap was truly part of a scam, it worked. Standard Metals received a payout of $9 million.

The Sunnyside Mine’s profit must have caught others’ eyes because, in 1984, Gerber Minerals Corp. leases the Gold King Mine. Gerber applies for a mining permit for the Gold King but not for a discharge permit because according to the application material for the site: “No drainage occurs from any of the portals — the district is deep-drained by the American Tunnel.”

In 1991, the Sunnyside Mine closed. As part of the Clean Water Act, nearby steams were tested for mineralization. The tests concluded that the Sunnyside Mine was responsible for the heavy minerals present in the streams. To avoid the looming prospect of becoming responsible for a Superfund site, the Sunnyside Gold Corporation agreed to block the flow of contaminated water from the mine entrance with a bulkhead (or a concrete plug). They also cleaned up the adjoining Gold King site and installed a water treatment plant.

Unfortunately, the treatment plant failed, and the plan to keep contamination from running out into the watershed only made things worse. The plugged ore shafts prevented leakage in the short term but over time they caused massive pressure to build up in the Sunnyside Mine and adjoining Gold King Mine.

In 1996, the American Tunnel is bulkheaded and sealed off. Reclamation agencies did not take into account that this would prevent the Gold King Mine from draining. Immediately following the closing of the American Tunnel, the EPA notes that the tiny trickle of water flowing out of the Gold King had increased in volume. This did not concern the EPA. They theorized the water discharging from the Gold King was groundwater, not realizing that the water was coming from the Sunnyside.

For the next several years, the EPA reports that discharge flowing from the Gold King was increasing both in dissolved mineral content and volume. By 2005, the mere trickle of discharge had increased to 200 gallons per minute or more. In 2009, the State Division of Mining Reclamation and Safety calls the Gold King, now dumping nearly 200,000 pounds of metals into the watershed per year, “one of the worst high quantity, poor water quality draining mines in the State of Colorado.” Fish populations downstream from the mine decline.

In 2011, the EPA takes its concerns over the Gold King Site to court. The agency receives a court order that forces the owner of the Gold King to allow the EPA onto the site to address water issues. The EPA begins work on the Gold King in 2014. At the time, draining flowing out of the Gold King had decreased from over 100 gallons per minute to just over 12 gallons per minute. Instead of suspecting that the water was backing up in the tunnel, the EPA attributes the change to “seasonal inflow to the mine.” The EPA completed two short hours of work excavating the portal, before deciding that there was no need to open up the portal to enter the mine and investigate the draining situation. This is one of the EPA’s biggest mistakes while working on the Gold King.

Four months before the blowout, a contractor finalizes the plans for work in the Gold King Mine. The plans note that due to the ceiling collapse in the mine, “Conditions may exist that could result in a blow-out of the blockages and cause a release of large volumes of contaminated mine waters and sediment from inside the mine.” The plans clearly state that to address this risk, the EPA should make sure to, “gradually lower the debris blockage.” Additionally, crews were to have pumps on hand to pump pool water out of the mine.

The Gold King Mine prior to the blowout. Photo taken Sept. 11, 2014. Courtesy of Environmental Protection Agency.

In August 2015, the On-Scene Coordinator for the operation called the Bureau of Reclamation. He had questions about plans for the site. He scheduled for a representative of the Bureau of Reclamation to inspect the site on August 14th, the day he’d return for vacation. In the following days, the On-Scene Coordinator leaves for his vacation. The EPA makes the reckless choice to carry on work in his absence.

The EPA proceeds to excavate the portal quickly and haphazardly. Notably, none of the crew was equipped with the pumps that the plan said would be crucial for draining the mine and avoiding a blowout. At 10:30 AM on August 5th, 2015, EPA contractors accidentally destroy the plug holding the water trapped inside the mine, triggering an uncontrolled rapid release of approximately 3 million gallons of orange water into the Animas River watershed. Within two days, the brassy water gushing out of the mine had reached multiple waterways across Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah. To add insult to injury, the EPA only warned these states of the spill over 24 hours after the incident occurred.

Entrance to the Gold King Mine during blowout. Photo taken August 6th, 2015.

Following the Gold King Spill, many people were furious with the EPA. Through their gross negligence, The EPA made effectively made the problems at the Gold King Mine much worse than when they arrived. After the blowout, the EPA requested an independent technical evaluation of the incident to understand what went wrong.

The Bureau of Reclamation review of the incident found that:

Conditions and actions that led to the Gold King Mine incident are not isolated or unique and in fact, are surprisingly prevalent. The standards of practice for reopening and remediating flooded inactive and abandoned mines are inconsistent from one agency to another. There are various guidelines for this type of work but there is little in actual written requirements that government agencies are required to follow when reopening an abandoned mine.

The Bureau of Reclamation considered other reclamation projects in the area, like the Red Mine or Bonita Mine, and concluded that a key difference between projects was that at the other mines, a drill rig was used to bore into the mine and observe the water levels before removing backfill. Operators at the Gold King considered doing this but skipped the step, which could have prevented the blowout incident.

An insightful report on the poor reclamation at Gold King states:

The incident at Gold King Mine is somewhat emblematic of the current state of practice in abandoned mine remediation. The current state of practice appears to focus attention on the environmental issues. Abandoned mine guidelines and manuals provide detailed guidance on environmental sampling, waste characterization, and water treatment, with little appreciation for the engineering complexity of some abandoned mine projects that often require, but do not receive, a significant level of expertise. In the case of the Gold King incident, as in many others, there was an absence of many essential things.

Unfortunately, there were many other oversights during the reclamation processes at the Gold King. In general, arbitrary reclamation efforts have become far too common today. Currently, in the Bonita Mining District alone, the Gold King is only one out of 48 sites set to be reclaimed. These uncoordinated efforts cost taxpayers around $80–85 million annually on hard rock mine remediation alone.

It is unjustifiable that the government wastes millions of taxpayer dollars on poorly planned and unsuccessful projects. The Gold King spill is just one mining site that reclamation has destroyed through negligence. The reality is that the contractors responsible for the actual legwork of reclamation are not mining engineers. They are not equipped to manage the complex structure of mines or to make decisions that will affect the lives and livelihoods of many. The simple truth is – mines are best left for miners to handle.