2022-12-05

By Stay Out Stay Alive

In beautiful high-country Colorado, the historic Prodigal Mine sits at an elevation of 8,600 feet in the Mummy Mountain Range. This impressive claim held a massive gold-and-silver-producing operation that left behind thousands of tons of gold-laden tailings. Not so long ago, the Prodigal property was the beloved home of many miners, who cherished every breath […]

In beautiful high-country Colorado, the historic Prodigal Mine sits at an elevation of 8,600 feet in the Mummy Mountain Range. This impressive claim held a massive gold-and-silver-producing operation that left behind thousands of tons of gold-laden tailings. Not so long ago, the Prodigal property was the beloved home of many miners, who cherished every breath of the petrichor and pine-scented air this property afforded. Unfortunately, today, the Prodigal site looks incredibly different than it did twenty-one years ago due to reclamation. Once you reach the eastern flank of Prohibition Mountain, the claim is easily locatable, as it sticks out like a sore thumb amongst the evergreen backdrop of the mountain. This is to say, the Prodigal is primarily distinguishable by its senseless destruction.

In 2001, the Colorado Division of Minerals and Geology chose to waste taxpayer dollars on the “reclamation” of the Prodigal Mine. When Gold Rush Expeditions, Inc.® surveyors visited the Prodigal mine site in 2015, they could tell which agency had reclaimed this site by the metal marker, located in a sizeable sloughed-off hole read, “Colorado Divisions of Minerals and Geology. 2001.” For obvious reasons, federal agencies have not advertised the reclamation work they did on this site, as money was spent, but nothing was really “reclaimed.” Like a tornado, the unbridled contractors responsible for the legwork of the reclamation tore through the Prodigal claim, indiscriminately destroying the site’s manmade structures along with its natural features.

As of 2015, the Prodigal Mine was a sorry sight. At first glance, you might have thought the lifeless property was the victim of a forest fire or an avalanche. A closer look revealed that the massive rotting trees strewn across the property were all purposely cut or pushed over with machinery. Fourteen years after the site’s reclamation, the area still looked like a garbage heap.

At the Prodigal’s entrance, a locked metal gate was installed to obstruct the public’s access to the mine’s underground workings. These types of gates are almost always installed without any semblance of justification. The Bureau of Land Management and Forest Services’ uncontested position that underground access goes beyond casual use allows them to revoke the public’s access to mines on public lands with these locked gates. Although most miners oppose reclamation entirely, many can concede that these metal gates are one of the least invasive reclamation techniques. By installing these pricey gates, federal agencies can meet their goal of protecting themselves from extremely rare lawsuits over injuries on public lands without permanently destroying a site’s value or accessibility for miners. The installation of this type of metal gate was the only measure that needed to be taken to keep the public out of the Prodigal Mine. Still, Colorado’s Division of Minerals and Geology did not stop there. In a show of excessive force and poor decision-making, contractors pushed over healthy trees and piled the debris over the entrance to the mine. This was not just reckless and unnecessary but genuinely asinine. The decision to shroud the mine entrance with giant decomposing trees has made the Prodigal site more dangerous. The unnatural garbage pile simultaneously calls attention to the mine entrance and threatens to fall on any curious onlookers who approach the entrance.

On the claim, Gold Rush Expeditions, Inc.® surveyors noticed a series of large sloughed-off holes, which were likely spots where reclamation contractors blew up supports with dynamite. This was a waste of time and resources, also not to mention dangerous! Like a group of adolescent boys, those in charge of the reclamation destroyed the workings of the Prodigal Mine for the sheer joy of seeing an explosion. These people were not mining engineers. Even for their own safety, they should have never tried collapsing any part of a mine.

The irony of the Colorado Division of Minerals and Geology’s strong anti-mining bias is not lost on us. As of 2015, the tailings at the Prodigal Mine were beautiful and obviously valuable. Gold Rush Expeditions, Inc. surveyors identified lots of visible gold in the piles. If it seems beyond counterproductive for an agency in charge of minerals and geology to suppress mining, that’s because it is. The agencies in charge of reclamation don’t have the authority to take away Americans’ right to mine public lands, but they get away with it all the time! Colorado is famous for its gold-rich ore. Instead of promoting resources, which would benefit citizens, these federal agencies destroy avenues of revenue. Many people in Colorado’s tiny mining towns could probably benefit enormously from new mining activity, yet sadly, those very people’s tax dollars are being spent to destroy mining.

One of the worst parts of the reclamation job at the Prodigal Mine is the blatant disrespect the Colorado Division of Minerals and Geology showed for the miners of a bygone era. Before reclamation, a historic miner’s cabin stood near the Prodigal Mine. During reclamation, contractors tossed tree limbs on the cabin and collapsed its structure. What remains of the cabin reveals that the cabin was special. The logs were carefully notched out with a knife or axe, which indicates it was built sometime between 1870 – 1900. A closer look at some of the logs reveals weathered names that miners once carved into the cabin walls. The reclaimed Prodigal Mine is a sad legacy to leave for the bygone miners of Colorado, who built the state on their backs.

Looking at what the government is doing to America’s remaining mining properties can feel despairing, but not all hope is lost for the mines that the Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management have prodigally destroyed. It will be up to miners to fix these sites. Although it will take time and effort to improve sites like the Prodigal Mine, we hope to see a future where claimants can render the destruction of reclamation null and reap profit from historic sites again.

2022-12-05

By Stay Out Stay Alive

If you are new to Stay Out Stay Alive, you might be wondering: What exactly is reclamation? How did it begin? Why should I care? Judging by the name, you might assume that mine reclamation is the process of modifying land that has been mined to an ecologically functional or economically usable state after mining […]

If you are new to Stay Out Stay Alive, you might be wondering: What exactly is reclamation? How did it begin? Why should I care?

Judging by the name, you might assume that mine reclamation is the process of modifying land that has been mined to an ecologically functional or economically usable state after mining operations are complete. Fifty years ago, you would have been correct about this. Unfortunately, today, the government has grossly corrupted the meaning of reclamation.

In the early days of the United States, hardrock gold mining settled the west, but coal was still king. Around 1939, demand for coal skyrocketed due to WWII. In response, many coal operations began mining as much as possible with little regard for environmental consequences. Unfortunately, this left behind a mess and proved terrible for the environment.

Coal mines are inherently dangerous, as they are designed to collapse in on themselves. In coal mines, coal is pulled out of seams in soft sedimentary rock. Miners accomplish this by cutting through the center of a coal layer. They leave columns of coal to support their drift. This is risky, as occasionally, columns collapse prematurely, killing miners. When the operation is done, the coal columns are supposed to be pulled over, causing the mountain to fall into the gap. In some cases, the last step of this process was ignored, which eventually caused abandoned coal mines to cave in on themselves, or worse, onto unexpecting explorers.

Aside from structural collapses, coal mines are innately hazardous since they can contain blackdamp. Blackdamp is a buildup of unbreathable gases, often found in poorly ventilated sections of coal mines. Coal mines are particularly susceptible to this phenomenon because coal naturally absorbs oxygen and exudes carbon dioxide. Blackdamp levels in abandoned coal mines can be fatal. Unfortunately, there are many stories about curious children or adults who have wandered into abandoned coal mines, breathed in too much blackdamp, lost consciousness, and then suffocated.

Outside of the inherent dangers of coal mines, poor practices often exacerbated risks. In many mines, fires were accidentally started underground. With tons of coal to pull energy from, these fires could burn for centuries, constantly releasing toxic greenhouse gasses into our atmosphere. These fires are difficult to extinguish and were often left burning.

By the end of the war, American citizens had begun worrying about the injuries, fatalities, and environmental effects associated with coal mines. In response, Congress enacted the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA) in 1977. The goal of this act was to promote the cleanup of abandoned coal mines that were left without adequate reclamation prior to August 3rd, 1977.

Following the creation of SMCRA, production fees were imposed on coal operations to finance reclamation projects. Initially, fees were set at 35 cents per ton for surface-mined coal and 15 cents per ton for coal mined underground. These production fees, along with late payments, interests, penalties, and administration charges were poured into America’s new Abandoned Mine Trust Fund. As this money was collected, the Office of Surface Mining began to dole out the funds to states and tribes with approved Abandoned Mine Reclamation Programs.

By 1980, states had cleaned up most of their coal sites, but they were still hungry for federal dollars. This gave rise to one of the most destructive programs that the country has ever enacted – the Abandoned Mining Lands (AML) program. With this program, the focus of reclamation shifted from closing abandoned coal mines to destroying viable hardrock mines.

Hardrock mines are very different from coal mines. In hardrock mines, adits and shafts are driven into stable, solid rock. These underground workings tunnel through the earth to reach mineral deposits. Unlike coal mines, hardrock mines are built to last. In fact, many of America’s oldest hardrock mines are still perfectly usable and full of value.

Since the beginning of the AML, the definition of what constitutes an abandoned mine has not always been straightforward. Each state has its own AML Task Force and the ability to define terms for itself. Originally, SMCRA Act defined abandoned mines as sites that meet the following three requirements:

1. Mining operations have ceased for a period of one year or more.

2. There are no approved financial assurances that are adequate to perform reclamation.

3. The mined lands are adversely affected by past mineral mining.

As the AML program aged, individual states began changing their definitions to expand what counts as an abandoned mine to increase the amount of funding they were eligible for. For example, in 1997, California’s AML Task Force updated their definition of abandoned mines as sites that meet all the following requirements:

1. Mining operations have ceased for a period of one year or more.

2. There is no interim management plan in effect; and

3. There are no approved financial assurances that are adequate to perform reclamation.

In California’s updated definition, abandoned mines did not need to be adversely affecting the environment to qualify for reclamation. This huge jump from a “coal mines are dangerous” attitude to an “all mines are dangerous” mindset rippled across other states looking to claim additional dollars from federal programs.

Ultimately, the AML program was created so that the United States Forest Service (USFS) and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), two organizations with strong anti-mining biases, could continue eating into the federal Abandoned Mine Trust Fund while destroying access to perfectly safe hardrock mines. These organizations have stated that the AML’s purpose is to “minimize the human health and safety hazards at abandoned mines while preserving the historic and wildlife habitat resources that they provide,” but this is far from the truth. Above all else, the ALM prioritizes keeping the public away from mines, almost always at the expense of destroying hardrock mines’ value and history.

The AML program gathers support through fearmongering. They perpetuate the myth that all mines “can expose anyone nearby to unexpected, serious danger” by maintaining that hardrock mines are just as dangerous as coal mines. This is an unsubstantiated lie. Although it is impossible to compare the number of people who have wandered safely in and out of an abandoned mine with the number of incidents, the sheer number of fatalities in hardrock mines compared to coal mines suggests that the latter is far more deadly.

Supposedly, the AML uses a “risk-based approach” to evaluate potential hazards in mines, although in the past few decades, it has become apparent that the only risks this government agency is concerned with are lawsuits. The program posts signs featuring its slogan, “Stay Out, Stay Alive,” near mines on public lands. Although the program claims that these signs are posted to protect the public from themselves, in reality, the AML is trying to protect itself from the public. Occasionally, citizens have sued the federal government over incidents that happened in mines on public land. In response, federal agencies have demonized mines. They tell citizens things like, “Stay Out, Stay Alive,” in hopes of instilling Americans with a fear of the career that built this country. The Stay Out Stay Alive campaign even targets children. Coloring books containing activities centered around the exaggerated dangers of abandoned mines are handed out in schools. It is telling that the AML program prioritizes propagating panic instead of equipping the public with mine safety knowledge. This tactic helps ensure that the AML can continue closing historical mining sites with little pushback.

Aside from equating coal mines with hardrock mines, the AML has created rumors and publicized misinformation about the supposed dangers of hardrock mines. One of the fabricated hazards the AML warns of is old dynamite. The program makes claims, such as, “experienced miners hesitate to handle old explosives. They realize the ingredients in explosives will deteriorate with age and can detonate at the slightest touch.” A quick Google search reveals many references to the dangers of old (or “sweating”) dynamite, although it is impossible to find even a single reference to old dynamite causing injury or death. Oddly enough, many online references appear to be repeating the exact warning from the same two sources - the USFS and the BLM. These sources’ message is clear, but their evidence is nonexistent. Dynamite becomes less explosive as it ages. According to a retired First Sergeant who served as an Explosive Ordnance Disposal Specialist, “even if old dynamite naturally crystalized, it would be mostly sodium and non-explosive.” He continued, arguing that “even if it naturally crystalized into something high grade, which it doesn't and won’t, sodium nitrate is hygroscopic and if exposed for any lengthy period would be desensitized and rendered harmless.”

As of 2022, the AML program continues to waste taxpayers’ money. They shell out cash for college students and amateur geologists to kick around rocks and play with dynamite on sites that have never posed danger to the public. These operations are expensive, yet they accomplish nothing but the senseless destruction of our country’s literal gold mines.

Sadly, it’s a largely overlooked fact that a majority of settlements in the west came about as a result of mining. Ranchers and cowboys didn’t just pop up and start breeding cattle. They started on small farms that were established near mining camps. These mining camps and towns gave the ranchers somewhere to sell their wares and someone to buy their cattle and crops. As time went on and the miners left for richer grounds, the ranchers expanded their reach. In many cases, ranchers took over abandoned mine lands and then applied for federal funding to compensate for existing damage on the land. Surprisingly this cash grab worked, and the federal government printed more cash for the farmers and ranchers who gobble up AML funds, all while cursing and defaming the mines that gave them their start.

Together, the Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service, the Environmental Protection Agency, and Interior's Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement (OSMRE) have spent, on average, about $287 million annually to address physical safety and environmental hazards at abandoned hardrock mines between 2008 and 2017. That means, in less than a decade, our country spent over 2.9 billion to keep the public out of valuable, workable mines. Agencies claim to be saving lives by reclaiming mines, but the truth is – not that many people are getting injured in mines. From 2008 – 2017, there was a total of 105 fatalities in abandoned mines. To put this number into perspective, in the same period, 302 people died from lightning strikes. That makes your odds of getting killed by lightning higher than the odds of dying in a mine.

For the sake of “environmentalism” and “safety”, the AML attempts to cover up and close off mines without considering the benefits of leaving the mines intact. The program caps and covers mines that miners spent their whole lives working in and effectively erases a part of their stories. Aside from the historical value that is lost, money is also lost when the AML shuts down mines. The AML doesn’t consider past production or future production potential when determining which mines to close off. This is infuriating and wasteful. Our survey team frequently observes rich sites that have been gated and reclaimed. These sites are a sad legacy to leave for men who spent their lives creating these mines. To work these sites in the future, America’s next generation of miners will be responsible for undoing the damage done by the AML program.

2022-12-13

By Stay Out Stay Alive

The Gold King Mine in Gunnison County, Colorado, is an excellent example of a historic mine that the Bureau of Land management ruined without fully understanding the mine’s history or potential for the future. Production at the Gold King Mine started in 1886. One report from 1902 says: “The largest producer in the county, both […]

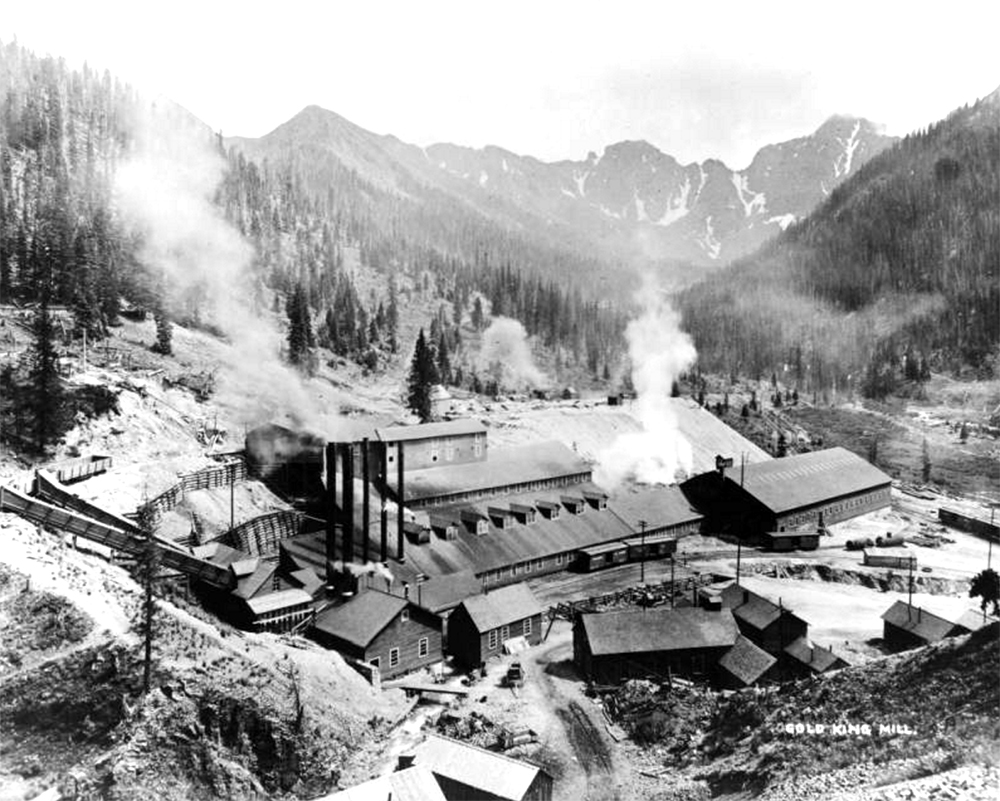

The Gold King Mine in Gunnison County, Colorado, is an excellent example of a historic mine that the Bureau of Land management ruined without fully understanding the mine’s history or potential for the future. Production at the Gold King Mine started in 1886. One report from 1902 says:

“The largest producer in the county, both in 'tonnage and values, is the Gold King, its ore mined and milled during the year reaching 72,455 tons. The mill of the company consists of an amalgamation and concentration plant, with a capacity of about 200 tons a day. The 80-stamps are of the rapid-drop pattern, weighing 850 pounds each, and the screens are especially made of copper wire for these batteries and have shown a remarkable life. The gold retorts sent from the mill have reached a total value of $400,000, and the concentrates shipped amounted to 14,428 tons, with a valuation of over $700,000.”

[caption id="attachment_247369" align="aligncenter" width="1000"] View of the Gold King Mill, in San Juan County Colorado; shows gold mine processing facilities, ore cars, cribbing, smokestacks, tailings, and mountain peaks. Taken between 1880 and 1920. Courtesy of the Denver Public - Western History Collection. [/caption]

View of the Gold King Mill, in San Juan County Colorado; shows gold mine processing facilities, ore cars, cribbing, smokestacks, tailings, and mountain peaks. Taken between 1880 and 1920. Courtesy of the Denver Public - Western History Collection. [/caption]

Other reports about the Gold King operation confirm how lucrative production was. By the time the Gold King ceased production in the late 1920s, the mine had produced more than 700,000 tons of gold, silver, lead, and copper ore, valued at $8.4 million. Reports also indicate that the grade of ore in the Gold King increased with depth, which might lead one to guess that there is still gold in the mine.

Following the closure of the Gold King Mine, the Sunnyside group of mines also shut down. This changed life in the nearby town of Silverton, Colorado. Once mining money stopped rolling in, the town’s economy began to rely on the tourism industry.

In 1960, operations at the Sunnyside Mine are revitalized. Miners began building an 11,000-foot-long tunnel connecting the American Tunnel to the Sunnyside Mine. The tunnel ran 860 feet under the Gold King Mine. Since the tunnel “deep drained” groundwater, the Gold King Mine became dry. In addition to water drainage, the tunnel provided gravity-assisted ore haulage for the Sunnyside group and helped revitalize mining around Silverton.

Years later, in 1972, on a Sunday morning, when no miners are working, the floor of Lake Emma collapses into the Sunnyside Mine, sending tens of millions of gallons of water gushing through the American Tunnel at Gladstone. This shut down the mine for months. To this day, some former employees are suspicious of the collapse, theorizing that it was planned by a struggling company looking for an insurance payout. For months before the collapse, engineers at the Sunnyside had warned management that they were cutting too close to the lake’s floor. If this mishap was truly part of a scam, it worked. Standard Metals received a payout of $9 million.

The Sunnyside Mine’s profit must have caught others’ eyes because, in 1984, Gerber Minerals Corp. leases the Gold King Mine. Gerber applies for a mining permit for the Gold King but not for a discharge permit because according to the application material for the site: “No drainage occurs from any of the portals — the district is deep-drained by the American Tunnel."

In 1991, the Sunnyside Mine closed. As part of the Clean Water Act, nearby steams were tested for mineralization. The tests concluded that the Sunnyside Mine was responsible for the heavy minerals present in the streams. To avoid the looming prospect of becoming responsible for a Superfund site, the Sunnyside Gold Corporation agreed to block the flow of contaminated water from the mine entrance with a bulkhead (or a concrete plug). They also cleaned up the adjoining Gold King site and installed a water treatment plant.

Unfortunately, the treatment plant failed, and the plan to keep contamination from running out into the watershed only made things worse. The plugged ore shafts prevented leakage in the short term but over time they caused massive pressure to build up in the Sunnyside Mine and adjoining Gold King Mine.

In 1996, the American Tunnel is bulkheaded and sealed off. Reclamation agencies did not take into account that this would prevent the Gold King Mine from draining. Immediately following the closing of the American Tunnel, the EPA notes that the tiny trickle of water flowing out of the Gold King had increased in volume. This did not concern the EPA. They theorized the water discharging from the Gold King was groundwater, not realizing that the water was coming from the Sunnyside.

For the next several years, the EPA reports that discharge flowing from the Gold King was increasing both in dissolved mineral content and volume. By 2005, the mere trickle of discharge had increased to 200 gallons per minute or more. In 2009, the State Division of Mining Reclamation and Safety calls the Gold King, now dumping nearly 200,000 pounds of metals into the watershed per year, “one of the worst high quantity, poor water quality draining mines in the State of Colorado.” Fish populations downstream from the mine decline.

In 2011, the EPA takes its concerns over the Gold King Site to court. The agency receives a court order that forces the owner of the Gold King to allow the EPA onto the site to address water issues. The EPA begins work on the Gold King in 2014. At the time, draining flowing out of the Gold King had decreased from over 100 gallons per minute to just over 12 gallons per minute. Instead of suspecting that the water was backing up in the tunnel, the EPA attributes the change to “seasonal inflow to the mine.” The EPA completed two short hours of work excavating the portal, before deciding that there was no need to open up the portal to enter the mine and investigate the draining situation. This is one of the EPA’s biggest mistakes while working on the Gold King.

Four months before the blowout, a contractor finalizes the plans for work in the Gold King Mine. The plans note that due to the ceiling collapse in the mine, “Conditions may exist that could result in a blow-out of the blockages and cause a release of large volumes of contaminated mine waters and sediment from inside the mine.” The plans clearly state that to address this risk, the EPA should make sure to, “gradually lower the debris blockage." Additionally, crews were to have pumps on hand to pump pool water out of the mine.

[caption id="attachment_247368" align="aligncenter" width="942"] The Gold King Mine prior to the blowout. Photo taken Sept. 11, 2014. Courtesy of Environmental Protection Agency. [/caption]

The Gold King Mine prior to the blowout. Photo taken Sept. 11, 2014. Courtesy of Environmental Protection Agency. [/caption]

In August 2015, the On-Scene Coordinator for the operation called the Bureau of Reclamation. He had questions about plans for the site. He scheduled for a representative of the Bureau of Reclamation to inspect the site on August 14th, the day he’d return for vacation. In the following days, the On-Scene Coordinator leaves for his vacation. The EPA makes the reckless choice to carry on work in his absence.

The EPA proceeds to excavate the portal quickly and haphazardly. Notably, none of the crew was equipped with the pumps that the plan said would be crucial for draining the mine and avoiding a blowout. At 10:30 AM on August 5th, 2015, EPA contractors accidentally destroy the plug holding the water trapped inside the mine, triggering an uncontrolled rapid release of approximately 3 million gallons of orange water into the Animas River watershed. Within two days, the brassy water gushing out of the mine had reached multiple waterways across Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah. To add insult to injury, the EPA only warned these states of the spill over 24 hours after the incident occurred.

[caption id="attachment_247378" align="alignright" width="525"] Entrance to the Gold King Mine during blowout. Photo taken August 6th, 2015. [/caption]

Entrance to the Gold King Mine during blowout. Photo taken August 6th, 2015. [/caption]

Following the Gold King Spill, many people were furious with the EPA. Through their gross negligence, The EPA made effectively made the problems at the Gold King Mine much worse than when they arrived. After the blowout, the EPA requested an independent technical evaluation of the incident to understand what went wrong.

The Bureau of Reclamation review of the incident found that:

Conditions and actions that led to the Gold King Mine incident are not isolated or unique and in fact, are surprisingly prevalent. The standards of practice for reopening and remediating flooded inactive and abandoned mines are inconsistent from one agency to another. There are various guidelines for this type of work but there is little in actual written requirements that government agencies are required to follow when reopening an abandoned mine.

The Bureau of Reclamation considered other reclamation projects in the area, like the Red Mine or Bonita Mine, and concluded that a key difference between projects was that at the other mines, a drill rig was used to bore into the mine and observe the water levels before removing backfill. Operators at the Gold King considered doing this but skipped the step, which could have prevented the blowout incident.

An insightful report on the poor reclamation at Gold King states:

The incident at Gold King Mine is somewhat emblematic of the current state of practice in abandoned mine remediation. The current state of practice appears to focus attention on the environmental issues. Abandoned mine guidelines and manuals provide detailed guidance on environmental sampling, waste characterization, and water treatment, with little appreciation for the engineering complexity of some abandoned mine projects that often require, but do not receive, a significant level of expertise. In the case of the Gold King incident, as in many others, there was an absence of many essential things.

Unfortunately, there were many other oversights during the reclamation processes at the Gold King. In general, arbitrary reclamation efforts have become far too common today. Currently, in the Bonita Mining District alone, the Gold King is only one out of 48 sites set to be reclaimed. These uncoordinated efforts cost taxpayers around $80–85 million annually on hard rock mine remediation alone.

It is unjustifiable that the government wastes millions of taxpayer dollars on poorly planned and unsuccessful projects. The Gold King spill is just one mining site that reclamation has destroyed through negligence. The reality is that the contractors responsible for the actual legwork of reclamation are not mining engineers. They are not equipped to manage the complex structure of mines or to make decisions that will affect the lives and livelihoods of many. The simple truth is – mines are best left for miners to handle.